One of the first signs their group might have a future came after a fall 1966 fraternity picnic on an island in the Detroit River that was accessible only by paddleboat. Soon enough Kramer linked up with enough like-minded musically inclined teenagers to form a proper band, which they dubbed the Motor City Five.

I looked up to them and wanted to be able to play at (their level), but my skill level was such that I was better off tackling the three chords that make up most rock ’n’ roll, not the six or seven chords that the Motown guys used. “They were trained, experienced jazz players.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16151184/waynekramer_c2a9jennyrisher_stratfoxtheatre_detroit.jpg)

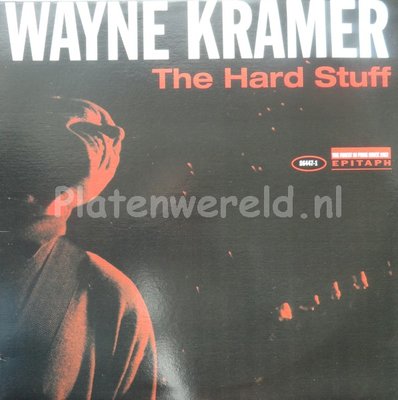

“We all aspired to play as well as the Motown musicians we just weren’t that accomplished,” he laughs. The dominance of Motown Records meant plenty of professionals around town to learn from, even for budding rock ’n’ rollers like Kramer. “It was perfectly in sync with my youth, and it could make you louder than anybody else.”ĭetroit in those days was prosperous, flush with good-paying jobs in the auto industry and a thriving music scene where experienced players and novices alike would congregate at music stores such as Town and Country or Capitol to talk shop, network and look for gigs. “It just spoke to me on a primal level it was to me the sound of liberation,” Kramer says. He fell even harder for the sound of the guitar once he heard it run through an amplifier. When she remarried, he and his stepfather didn’t exactly get along - in fact, Kramer says the stepfather was at times abusive, to both him and his sister - but the older man was also a musician whose use of the guitar while courting his mother didn’t escape Kramer’s attention. His father ran out on the family early on, but his mother operated a successful beauty parlor she eventually grew into a franchise. “I wanted my son to know the road his dad traveled to get to him.” Kramer was stuck on an ending at first, he admits, but realized the symbolism was perfect. Eventually he emerged as a hero to a younger generation of rockers on his 1995 record for Epitaph Records, also called “The Hard Stuff” and in 2014 cut an ambitious jazz album, “Lexington,” that doubled as the soundtrack to a PBS documentary about the drug war.īut what put him in a memoir-writing mood was the birth of his son, now 5 years old. Kramer’s new autobiography, “The Hard Stuff: Dope, Crime, the MC5 and My Life of Impossibilities,” recounts in harrowing detail his years of drug addiction and criminal activity following the MC5’s breakup, which bottomed out with federal prison time. But all those cheers came at a steep price.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)